【评论】映红地球的一片火焰

来源:《纽约时报》作者:马修.艾德朗(美国亚洲博物馆馆长

车开出北京城近两个小时,我们的司机不时要停下来找路。沿途经过许多新的开发区,有时还真不知道身在何处。也许对于我们来说并不为过,因为我们是去拜访贾又福――当代世界上最为著名的画家之一,而知道他的美国人却为数不多。

我们沿着没有路灯的公路驶入空旷阴冷、烟雾弥漫的郊外,除了高速上的白线到处一片黑暗,临近住地,眼前蓦然出现一处犹如迪斯尼乐园主题公园般的住宅区。社区入口是屹然高耸、明亮而华丽的大门,飞檐雕栋,朱红的大门柱犹如现代的宏伟大殿,富有中国古典传统色彩,神秘而庄严。门口警卫身着制服,佩带半自动枪。

我问身边的马欣乐,这位贾先生的朋友和学生,常住上海的画家,“警卫为何佩带枪枝?”他说这是北京城区最早开发的高档别墅社区,里面住有不少重要人物,包括某些国家领导人。接待的警卫笑容可拘,他与主人取得联系后飞身骑上一辆摩托车,帮我们带路,否则还真会身陷迷宫。园内多是砖石和大理石结构的欧式别墅,当我们一路驶过时路边的保卫人员挥手致意。

贾又福的房子一片光亮,在房子右侧的车道旁竖着白色帐蓬,里面停着一辆我从未见过的古怪车型,好象一辆高尔夫车但要复杂一些,上面有个白色汽球一样的园顶子,站在旁边的正是贾又福先生。

下车的时候,他的妻子上前迎接我们,还有卫卫,个头高大的都博曼,一种德国的良种猎犬,她警觉地挡在贾先生身前,不停地向我这个“不速之客”发出警告,贾先生拍了拍它的身子,她就立刻变得温顺起来。

贾又福64岁,按中国的计算方法65岁。他是在一个具有连续三千年绘画传统国家里一个最为重要的画家之一。他身着黑色的中式休闲装,一头银发,神态沉稳自诺,谦逊而热情。我们晚到了。马欣乐是位画坛的后起之秀,贾先生也期待这位年轻朋友的到来,谈书论画。身体的不适使他近年少于外出,但作为一名教书几十载的老师,他善于教诲,且致致不倦。

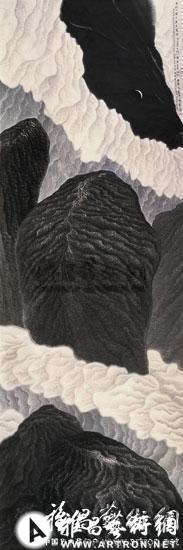

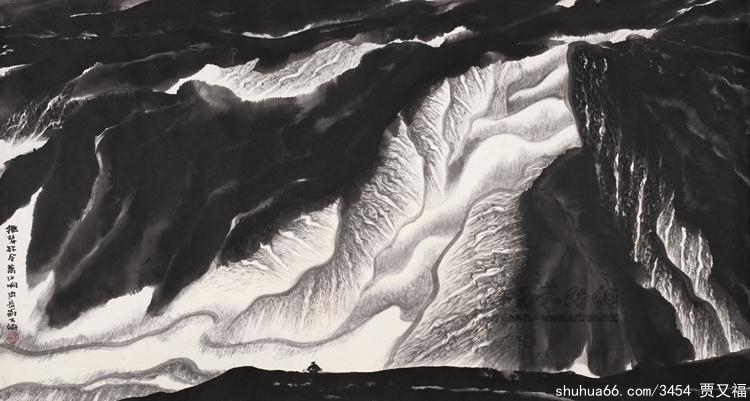

曾有人告诉我贾先生的住宅是一座宏伟高大的五层楼宫殿,看来言传不可信。他的室内舒适、宽畅、朴素而温馨。我们随贾先生来到他的画室,并在藏画室观看了他的近年新作。几十年来他一直在画太行山。较早的作品还可以看出其中所描绘的地域性,如今升华到中国传统绘画中对神品、逸品层次的表现。他如痴如醉,情随意流、使精神凌驾扵万物之上,游刃扵创作的最佳境界。

自从九世纪大画家苏轼有“论画以形似,见与儿童邻”的高论、画家的作品则着重于表现自我和天人合一。中国画以表现大自然为契合点,并进一步发展为对于精神境界的表现,情境交融,通过修养的积累和智慧的超越从而达到精神的升华和艺术的升华。可以说贾又福是继承和发展千年中华传统绘画艺术的最佳典范。

贾又福仍然是位传统的山水画家。在他展示那些手卷及挂轴时,他告诉我,他的笔意墨趣源自老师及画界前辈大师,但又富有自己的创新,形成有自己独特的风貌。他的恩师之一李可染先生曾告诫他要索取古人的绘画精神,为己所用。“所要者魂,可贵者胆。”习古人但要有自我,这些近年新作奔腾有势,凌跨群雄。他那具有冲击力的雄劲笔力,别具一格的沉厚墨气和不同凡响的画面魄力,往往使有些人觉得他是否应归属于深受西方绘画影响的新现代派画家。

通过这些作品,我感到他的现代美学思想完全是在传统笔墨的基础上的体现和开拓,是他在20世纪和21世纪将中国传统绘画推向一个新的高度和层面,并对现代中国山水画的创作产生了举足轻重的影响。

几十年来,太行山就象他心目中的宇宙,大不可及,深不可测。那些山民在他的作品中显得遥远而藐小,然而他们就像文中的省略号,在画面中意深味长…….

他的绘画是典型的笔墨之作。中国画的意义远远要超越出表现自我精神和思想,陈述过去和现在,它是笔墨形式与内存精神的完美统一,给人的更高的精神享受。它又是探讨的题材,而不仅是可以悬挂在墙上的饰物。你可以欣赏它,感知它,争论它,它蕴藏着画家的灵魂与情感,将人与自然的融合与精神揉为一体。

贾先生非常清楚,中国绘画传统要求“天人相合,心物相合,物物相合。”他心境浩淼,精神与天地往来。在他的作品中,要将这种溶合体现在每一个笔触,每一笔都体现着他对这种溶合的理解,独具匠心,就象歌唱家的声音,是一种叙发,又是一种无法再现的永恒。

贾又福深入太行山四十余次,每次都有新的领悟和不同的收获。“下笔之前,要胸有成竹,知道自己想要表现什么,也有的时候并非所愿,画出来的不能尽然表达自己的思想和感受,或出乎意料,这会让我更深一步地去探索,去寻求笔墨中的奥妙,迁想妙得,中得心源。”

在中国画里,气和韵的表现尤为主要。大自然、大世界、画家本身都具备一种气韵和精神,这些都应当在画家的笔墨挥洒中得到体现,在书法的运笔过程中自然而然地渗化出来。故此中国画的创作过程有时并不叫画,而称之为写。

中国画家在古代就懂的“竖划三寸,当千仞之高;横墨数尺,体百里之迥。”贾又福的画有时篇幅不大,但所表现的题材巍然壮观。墨笔经过他挥洒,山脉重峦叠嶂,如烟成霭,河谷逶迤绵延,如音栖弦、真是气象万千。有时一牙小月高悬天空,有时游离于山下或涧旁……对于他来说,月亮画在地平线之上或以下。并不重要,重要的是将它画在你心中认为重要而合理的地位。在他的作品中,天和水也许会上下倒置,抽象的笔墨就象在表现一种原始的、巨大的、没有生命的历史空间。在有些表现黄昏落日景象的作品中,橘黄和大红的色彩横扫画面,就象映红地球的一片火焰;有的时候,丰富多变的墨色表现了只有在安塞尔·亚当斯摄影作品中才体味到的玄奥、寂静和神秘。对于他来说,创作是对已经逝去的一种意念的重新理解和表现。有时也需要和想法保持一定距离,不要太近,最重要的不是想法而是感情。他是用笔墨将自然情怀与人的精神气度凝为一体,他的画仿佛魂系大千世界,时醒时梦,扑朔迷离,赞颂着永恒的生命与不朽精神的神奇。

他指着一幅象是美国大峡谷的笔墨山水画的一部分,其中的云和水也可以想像成天空,“看似云彩,又似气和水,似有不同而又相同,就像生和死,阴和阳。画重在心灵,以我的心灵更求古人的心灵,是天地间之真气。”其苍茫润泽之气,腾腾欲动,撼人心弦。在他的内心深处,他用自己独特的绘画语言建造了一个新的奥妙世界。

贾又福往往觉得力不从心,要画的东西太多,要深入研究的东西太多。现在不能像从前一样,时常深入山区,日行几十里,他甚至不愿经常奔波于北京城区去他执教数十年的中央美术学院。60年代他曾经是那里的学生,如今博士研究生们来登门求教。

欣乐打开了他的一些花卉近作,贾先生详细观看每一幅作品,赞赏其画作的精良墨笔和超俗的构图,并指出了一些用笔上的缺欠与改进方法,并让欣乐集中精力,不要选材太广,这样才能精益求精。欣乐坚实的传统画功底及良好的悟性使他感到欣慰和高兴。

贾先生希望创作更多的作品,但并非易了。除了教授绘画艺术,他的生命就是绘画创作。卫卫又跑过来看我们,高兴地依偎在主人的身边,在没有窗子的地下室她似乎觉的主人更加安全,也显得轻松而随和。她欢快地嗅一嗅每个人,也让我嗅嗅她的鼻子。贾先生很高兴看到她,也很高兴和我们一起谈论绘画。

时至深夜,我们和贾又福,他的妻子还有卫卫一一惜别。司机穿过身着红、金色相间制服的保安人员,轻松地开出了大门。开出好久也没有遇到其它的车辆,外面也无路灯,墨黑的夜就象一顶斗篷笼罩着我们,巨大无比,然而我还是感觉到它并没有像贾又福的画那么巨大,那么深沉和雄伟。

马欣乐译自《纽约时报》美东新闻与文化生活导报《长船要闻》 2007年2月2日版

Fire on the Earth

by Matthew Edlund, Curator of Asian Art Museum of Sarasota

We’ve been driving for two hours beyond Beijing. The taxi driver frequently stops to find the way. There are so many new developments you can never be sure where we are. It seems appropriate as we try to find Jia Youfu, one of the most important artists in the world that Americans know nothing about.

We move across the unlit foothills into a dank, smoggy darkness, the only feature the white line of the road. When the gate of Jia’s complex appears, it appears like the opening to a theme park. The tall, bright, gaudy gate tower is topped by swaggering eaves , painted the vermillion colors of a modernized temple. But the guards’ military uniforms, and their submachine guns, are real.

I ask Ma Xinle, the Shanghai painter and friend of Jia, why the guns? There are important people living in this complex, one of the first high end suburban developments built in the Beijing foothills. Some are high party officials.

The guard’s smile is infectious. Putting away the submachine gun, he mounts a scooter to take us to Jia’s home, which we’d never find ourselves. The complex is filled with substantial brick and marble homes, parolled by guards in red livery and gold braid. They wave as we go by.

Jia’s house is well lighted. Curled on the side of the driveway is a white canopy. Beneath is a vehicle I have never seen, a cross between a smart car and a golf cart with a high white, balloon shaped top. Standing next to it is Jia. .

As we get out we are greeted by his wife, coming out of the house, and by Wei Wei, a tall Doberman who cannot stop barking. Wei Wei protectively moves in front of Jia, menacingly thrusting his muzzle, but turns friendly as Jia calms him.

Jia Youfu is 64, 65 by Chinese count. He is one of the most important painters in a country with a continuous 3,000 year tradition of painting, a tradition he sees himself a part of in every way. He is casually dressed in black, his hair all white. His manner is modest, welcoming, and sober. We are late. Ma is a rising painter, and Jia is looking forward to meeting a young friend and talking about painting. Heart disease prevents him from traveling very much, but as a teacher of many decades, he enjoys meeting the new generation.

I have been told Jia’s house is a palatial five story mansion. The rumor is wrong. The home is comfortable and spare, almost austere. We retire to the basement. Jia’s brings out paintings of recent years.

For forty years, he has painted the Taihang Mountains. At first you might have been able to tell some of locations, but quickly the paintings became what Chinese paintings normally are, landscapes of the mind. Ever since the great painter and statesman Su Shi nine hundred years ago that purely representational painting is for children, what matters is the painter’s expression. Chinese painting has used nature as the starting point, but then gone much further. The credo of the Abstract Expressionists would not have been so foreign to Chinese painters of the eleventh century.

Jia is a traditional painters. As he spreads out handscrolls and hanging scrolls, he tells me his brush ideas are those of his teachers and forebears, but his own technique is unique. One of his great teachers, Li Keran, told him that he must always learn from the spirit of the past, but have the bravery to make things his own. Jia is troubled that his powerful, innovative technique leads some to think him a Western style, contemporary painter.

For decades he has represented the Taihang mountains as a cosmos. People live there, but man is small to the point of near invisibility. Peasants have to walk four hours to get the wood they need for fires, he tells me, and carry it for four hours back down. Nature is high, wide, and deep, and harsh. Life in the Taihang mountains is hard.

“At first I painted the mountains, their spirit. Then I painted my feeling, my response to them. Now I think the two, my spirit and the spirit of the mountins, become one ,” Jia says.

The paintings are mostly brush and ink. Chinese paintings are more than expressions of individual spirit and thought, statements of the present and the past. They are also objects of discussion. You don’t just put paintings on the wall. You watch them, feel them, argue about them. When things get heated, you may try to talk to them.

Jia is well aware that the Chinese painting tradition requires that nature, man, the spirit of life be engaged through every stroke. Each brush stroke is an expression of the person making it, unique as a singing voice, both a permanent mark and a performance. Jia has been to the Taihang mountains more than 40 times. Each time is different. Each time he finds something else.

“Before I paint, I know in my mind what I will paint. Yet sometimes what comes out is not what I felt, not what I thought. This is a surprise. It lets me go deeper.”

In Chinese painting, qi, or spirit, is always present. There is the spirit of nature, of the world, of the painter. Each should live within the the writing of brush on ink. Coming from the strokes of calligraphy, which also started with the natural world, Chinese paintings are sometimes said to be written, not painted.

One ancient goal of Chinese painting was to express a thousand miles (li) in each foot of the painting. Jia’s paintings are sometimes small, but not his subject. Though using brush and ink, mountain ranges, rivers, and sky coalesce. Sometimes a tiny moon flies, below, beside, above the mountains. It doesn’t matter where the moon is, above the horizon, or below the earth, Jia tells me. It should just be where it belongs.

In his paintings, sky and water reverse places. Abstract lines of ink are physical fields recreating a planet which is primordial, vast, inhumanly monumental, unrelenting. Sometimes the red and orange of sunsets sweep like a fire on the earth, othertimes the many different colors of black ink form giant vistas which Ansel Adams could identify. Jia wants to paint a creative reinterpretation of ideas of the past, though not the ideas themselves. “You have to have a distance from ideas. Not too close. What’s most valuable is not the ideas, but the feeling.”

He points out part of a landscape that looks like an ink and brush Grand Canyon. Land and water could just as easily be sky. “It’s like clouds. They are air and water. Different, but the same. Like life and death.”

Death is not far away. I feel Jia’s pulse, the irregularly irregular beat of atrial fibrillation. As a Western doctor, I tell him there are different treatments for his condition. At one of the great artists of China, he is taken care of by top traditional doctors.

Jia doesn’t have the strength he’d like. It’s hard to get to the mountains now, almost impossible to climb them. It’s even arduous to get to Beijing, where he has long been a revered teacher at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, where he himself was a student in the sixties. Now students come to him.

Ma unrolls some of his own scrolls. Jia discusses them, firm but critical, telling Ma to go deeper, to specialize in one topic like he did. He is more voluble now, smiling happily as he looks at Ma’s paintings.

Jia wants to paint more, but it’s hard. Painting is pretty much all he wants to do, except for teaching others about it.

Wei Wei rejoins us, happy to be with his master. In the windowless basement he is no longer so protective. He sniffs everyone happily, allowing me to sniff his nose in turn. Jia is enlivened to see him again, happier still to talk with Ma about painting.

It’s late in the night when we leave. We wave at Jia, Wei Wei, and his wife.

The driver finds his way past the brisking walking red and gold clad guards, and we signal the well armed sentries at the gate.

For a long time there are no others cars, no lights. The inky black night falls over us like a cold cloak. The night is vast. Yet somehow the night doesn’t feel as big as Jia’s paintings.

来源:《纽约时报》作者:马修.艾德朗(美国亚洲博物馆馆长

车开出北京城近两个小时,我们的司机不时要停下来找路。沿途经过许多新的开发区,有时还真不知道身在何处。也许对于我们来说并不为过,因为我们是去拜访贾又福――当代世界上最为著名的画家之一,而知道他的美国人却为数不多。

我们沿着没有路灯的公路驶入空旷阴冷、烟雾弥漫的郊外,除了高速上的白线到处一片黑暗,临近住地,眼前蓦然出现一处犹如迪斯尼乐园主题公园般的住宅区。社区入口是屹然高耸、明亮而华丽的大门,飞檐雕栋,朱红的大门柱犹如现代的宏伟大殿,富有中国古典传统色彩,神秘而庄严。门口警卫身着制服,佩带半自动枪。

我问身边的马欣乐,这位贾先生的朋友和学生,常住上海的画家,“警卫为何佩带枪枝?”他说这是北京城区最早开发的高档别墅社区,里面住有不少重要人物,包括某些国家领导人。接待的警卫笑容可拘,他与主人取得联系后飞身骑上一辆摩托车,帮我们带路,否则还真会身陷迷宫。园内多是砖石和大理石结构的欧式别墅,当我们一路驶过时路边的保卫人员挥手致意。

贾又福的房子一片光亮,在房子右侧的车道旁竖着白色帐蓬,里面停着一辆我从未见过的古怪车型,好象一辆高尔夫车但要复杂一些,上面有个白色汽球一样的园顶子,站在旁边的正是贾又福先生。

下车的时候,他的妻子上前迎接我们,还有卫卫,个头高大的都博曼,一种德国的良种猎犬,她警觉地挡在贾先生身前,不停地向我这个“不速之客”发出警告,贾先生拍了拍它的身子,她就立刻变得温顺起来。

贾又福64岁,按中国的计算方法65岁。他是在一个具有连续三千年绘画传统国家里一个最为重要的画家之一。他身着黑色的中式休闲装,一头银发,神态沉稳自诺,谦逊而热情。我们晚到了。马欣乐是位画坛的后起之秀,贾先生也期待这位年轻朋友的到来,谈书论画。身体的不适使他近年少于外出,但作为一名教书几十载的老师,他善于教诲,且致致不倦。

曾有人告诉我贾先生的住宅是一座宏伟高大的五层楼宫殿,看来言传不可信。他的室内舒适、宽畅、朴素而温馨。我们随贾先生来到他的画室,并在藏画室观看了他的近年新作。几十年来他一直在画太行山。较早的作品还可以看出其中所描绘的地域性,如今升华到中国传统绘画中对神品、逸品层次的表现。他如痴如醉,情随意流、使精神凌驾扵万物之上,游刃扵创作的最佳境界。

自从九世纪大画家苏轼有“论画以形似,见与儿童邻”的高论、画家的作品则着重于表现自我和天人合一。中国画以表现大自然为契合点,并进一步发展为对于精神境界的表现,情境交融,通过修养的积累和智慧的超越从而达到精神的升华和艺术的升华。可以说贾又福是继承和发展千年中华传统绘画艺术的最佳典范。

贾又福仍然是位传统的山水画家。在他展示那些手卷及挂轴时,他告诉我,他的笔意墨趣源自老师及画界前辈大师,但又富有自己的创新,形成有自己独特的风貌。他的恩师之一李可染先生曾告诫他要索取古人的绘画精神,为己所用。“所要者魂,可贵者胆。”习古人但要有自我,这些近年新作奔腾有势,凌跨群雄。他那具有冲击力的雄劲笔力,别具一格的沉厚墨气和不同凡响的画面魄力,往往使有些人觉得他是否应归属于深受西方绘画影响的新现代派画家。

通过这些作品,我感到他的现代美学思想完全是在传统笔墨的基础上的体现和开拓,是他在20世纪和21世纪将中国传统绘画推向一个新的高度和层面,并对现代中国山水画的创作产生了举足轻重的影响。

几十年来,太行山就象他心目中的宇宙,大不可及,深不可测。那些山民在他的作品中显得遥远而藐小,然而他们就像文中的省略号,在画面中意深味长…….

他的绘画是典型的笔墨之作。中国画的意义远远要超越出表现自我精神和思想,陈述过去和现在,它是笔墨形式与内存精神的完美统一,给人的更高的精神享受。它又是探讨的题材,而不仅是可以悬挂在墙上的饰物。你可以欣赏它,感知它,争论它,它蕴藏着画家的灵魂与情感,将人与自然的融合与精神揉为一体。

贾先生非常清楚,中国绘画传统要求“天人相合,心物相合,物物相合。”他心境浩淼,精神与天地往来。在他的作品中,要将这种溶合体现在每一个笔触,每一笔都体现着他对这种溶合的理解,独具匠心,就象歌唱家的声音,是一种叙发,又是一种无法再现的永恒。

贾又福深入太行山四十余次,每次都有新的领悟和不同的收获。“下笔之前,要胸有成竹,知道自己想要表现什么,也有的时候并非所愿,画出来的不能尽然表达自己的思想和感受,或出乎意料,这会让我更深一步地去探索,去寻求笔墨中的奥妙,迁想妙得,中得心源。”

在中国画里,气和韵的表现尤为主要。大自然、大世界、画家本身都具备一种气韵和精神,这些都应当在画家的笔墨挥洒中得到体现,在书法的运笔过程中自然而然地渗化出来。故此中国画的创作过程有时并不叫画,而称之为写。

中国画家在古代就懂的“竖划三寸,当千仞之高;横墨数尺,体百里之迥。”贾又福的画有时篇幅不大,但所表现的题材巍然壮观。墨笔经过他挥洒,山脉重峦叠嶂,如烟成霭,河谷逶迤绵延,如音栖弦、真是气象万千。有时一牙小月高悬天空,有时游离于山下或涧旁……对于他来说,月亮画在地平线之上或以下。并不重要,重要的是将它画在你心中认为重要而合理的地位。在他的作品中,天和水也许会上下倒置,抽象的笔墨就象在表现一种原始的、巨大的、没有生命的历史空间。在有些表现黄昏落日景象的作品中,橘黄和大红的色彩横扫画面,就象映红地球的一片火焰;有的时候,丰富多变的墨色表现了只有在安塞尔·亚当斯摄影作品中才体味到的玄奥、寂静和神秘。对于他来说,创作是对已经逝去的一种意念的重新理解和表现。有时也需要和想法保持一定距离,不要太近,最重要的不是想法而是感情。他是用笔墨将自然情怀与人的精神气度凝为一体,他的画仿佛魂系大千世界,时醒时梦,扑朔迷离,赞颂着永恒的生命与不朽精神的神奇。

他指着一幅象是美国大峡谷的笔墨山水画的一部分,其中的云和水也可以想像成天空,“看似云彩,又似气和水,似有不同而又相同,就像生和死,阴和阳。画重在心灵,以我的心灵更求古人的心灵,是天地间之真气。”其苍茫润泽之气,腾腾欲动,撼人心弦。在他的内心深处,他用自己独特的绘画语言建造了一个新的奥妙世界。

贾又福往往觉得力不从心,要画的东西太多,要深入研究的东西太多。现在不能像从前一样,时常深入山区,日行几十里,他甚至不愿经常奔波于北京城区去他执教数十年的中央美术学院。60年代他曾经是那里的学生,如今博士研究生们来登门求教。

欣乐打开了他的一些花卉近作,贾先生详细观看每一幅作品,赞赏其画作的精良墨笔和超俗的构图,并指出了一些用笔上的缺欠与改进方法,并让欣乐集中精力,不要选材太广,这样才能精益求精。欣乐坚实的传统画功底及良好的悟性使他感到欣慰和高兴。

贾先生希望创作更多的作品,但并非易了。除了教授绘画艺术,他的生命就是绘画创作。卫卫又跑过来看我们,高兴地依偎在主人的身边,在没有窗子的地下室她似乎觉的主人更加安全,也显得轻松而随和。她欢快地嗅一嗅每个人,也让我嗅嗅她的鼻子。贾先生很高兴看到她,也很高兴和我们一起谈论绘画。

时至深夜,我们和贾又福,他的妻子还有卫卫一一惜别。司机穿过身着红、金色相间制服的保安人员,轻松地开出了大门。开出好久也没有遇到其它的车辆,外面也无路灯,墨黑的夜就象一顶斗篷笼罩着我们,巨大无比,然而我还是感觉到它并没有像贾又福的画那么巨大,那么深沉和雄伟。

马欣乐译自《纽约时报》美东新闻与文化生活导报《长船要闻》 2007年2月2日版

Fire on the Earth

by Matthew Edlund, Curator of Asian Art Museum of Sarasota

We’ve been driving for two hours beyond Beijing. The taxi driver frequently stops to find the way. There are so many new developments you can never be sure where we are. It seems appropriate as we try to find Jia Youfu, one of the most important artists in the world that Americans know nothing about.

We move across the unlit foothills into a dank, smoggy darkness, the only feature the white line of the road. When the gate of Jia’s complex appears, it appears like the opening to a theme park. The tall, bright, gaudy gate tower is topped by swaggering eaves , painted the vermillion colors of a modernized temple. But the guards’ military uniforms, and their submachine guns, are real.

I ask Ma Xinle, the Shanghai painter and friend of Jia, why the guns? There are important people living in this complex, one of the first high end suburban developments built in the Beijing foothills. Some are high party officials.

The guard’s smile is infectious. Putting away the submachine gun, he mounts a scooter to take us to Jia’s home, which we’d never find ourselves. The complex is filled with substantial brick and marble homes, parolled by guards in red livery and gold braid. They wave as we go by.

Jia’s house is well lighted. Curled on the side of the driveway is a white canopy. Beneath is a vehicle I have never seen, a cross between a smart car and a golf cart with a high white, balloon shaped top. Standing next to it is Jia. .

As we get out we are greeted by his wife, coming out of the house, and by Wei Wei, a tall Doberman who cannot stop barking. Wei Wei protectively moves in front of Jia, menacingly thrusting his muzzle, but turns friendly as Jia calms him.

Jia Youfu is 64, 65 by Chinese count. He is one of the most important painters in a country with a continuous 3,000 year tradition of painting, a tradition he sees himself a part of in every way. He is casually dressed in black, his hair all white. His manner is modest, welcoming, and sober. We are late. Ma is a rising painter, and Jia is looking forward to meeting a young friend and talking about painting. Heart disease prevents him from traveling very much, but as a teacher of many decades, he enjoys meeting the new generation.

I have been told Jia’s house is a palatial five story mansion. The rumor is wrong. The home is comfortable and spare, almost austere. We retire to the basement. Jia’s brings out paintings of recent years.

For forty years, he has painted the Taihang Mountains. At first you might have been able to tell some of locations, but quickly the paintings became what Chinese paintings normally are, landscapes of the mind. Ever since the great painter and statesman Su Shi nine hundred years ago that purely representational painting is for children, what matters is the painter’s expression. Chinese painting has used nature as the starting point, but then gone much further. The credo of the Abstract Expressionists would not have been so foreign to Chinese painters of the eleventh century.

Jia is a traditional painters. As he spreads out handscrolls and hanging scrolls, he tells me his brush ideas are those of his teachers and forebears, but his own technique is unique. One of his great teachers, Li Keran, told him that he must always learn from the spirit of the past, but have the bravery to make things his own. Jia is troubled that his powerful, innovative technique leads some to think him a Western style, contemporary painter.

For decades he has represented the Taihang mountains as a cosmos. People live there, but man is small to the point of near invisibility. Peasants have to walk four hours to get the wood they need for fires, he tells me, and carry it for four hours back down. Nature is high, wide, and deep, and harsh. Life in the Taihang mountains is hard.

“At first I painted the mountains, their spirit. Then I painted my feeling, my response to them. Now I think the two, my spirit and the spirit of the mountins, become one ,” Jia says.

The paintings are mostly brush and ink. Chinese paintings are more than expressions of individual spirit and thought, statements of the present and the past. They are also objects of discussion. You don’t just put paintings on the wall. You watch them, feel them, argue about them. When things get heated, you may try to talk to them.

Jia is well aware that the Chinese painting tradition requires that nature, man, the spirit of life be engaged through every stroke. Each brush stroke is an expression of the person making it, unique as a singing voice, both a permanent mark and a performance. Jia has been to the Taihang mountains more than 40 times. Each time is different. Each time he finds something else.

“Before I paint, I know in my mind what I will paint. Yet sometimes what comes out is not what I felt, not what I thought. This is a surprise. It lets me go deeper.”

In Chinese painting, qi, or spirit, is always present. There is the spirit of nature, of the world, of the painter. Each should live within the the writing of brush on ink. Coming from the strokes of calligraphy, which also started with the natural world, Chinese paintings are sometimes said to be written, not painted.

One ancient goal of Chinese painting was to express a thousand miles (li) in each foot of the painting. Jia’s paintings are sometimes small, but not his subject. Though using brush and ink, mountain ranges, rivers, and sky coalesce. Sometimes a tiny moon flies, below, beside, above the mountains. It doesn’t matter where the moon is, above the horizon, or below the earth, Jia tells me. It should just be where it belongs.

In his paintings, sky and water reverse places. Abstract lines of ink are physical fields recreating a planet which is primordial, vast, inhumanly monumental, unrelenting. Sometimes the red and orange of sunsets sweep like a fire on the earth, othertimes the many different colors of black ink form giant vistas which Ansel Adams could identify. Jia wants to paint a creative reinterpretation of ideas of the past, though not the ideas themselves. “You have to have a distance from ideas. Not too close. What’s most valuable is not the ideas, but the feeling.”

He points out part of a landscape that looks like an ink and brush Grand Canyon. Land and water could just as easily be sky. “It’s like clouds. They are air and water. Different, but the same. Like life and death.”

Death is not far away. I feel Jia’s pulse, the irregularly irregular beat of atrial fibrillation. As a Western doctor, I tell him there are different treatments for his condition. At one of the great artists of China, he is taken care of by top traditional doctors.

Jia doesn’t have the strength he’d like. It’s hard to get to the mountains now, almost impossible to climb them. It’s even arduous to get to Beijing, where he has long been a revered teacher at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, where he himself was a student in the sixties. Now students come to him.

Ma unrolls some of his own scrolls. Jia discusses them, firm but critical, telling Ma to go deeper, to specialize in one topic like he did. He is more voluble now, smiling happily as he looks at Ma’s paintings.

Jia wants to paint more, but it’s hard. Painting is pretty much all he wants to do, except for teaching others about it.

Wei Wei rejoins us, happy to be with his master. In the windowless basement he is no longer so protective. He sniffs everyone happily, allowing me to sniff his nose in turn. Jia is enlivened to see him again, happier still to talk with Ma about painting.

It’s late in the night when we leave. We wave at Jia, Wei Wei, and his wife.

The driver finds his way past the brisking walking red and gold clad guards, and we signal the well armed sentries at the gate.

For a long time there are no others cars, no lights. The inky black night falls over us like a cold cloak. The night is vast. Yet somehow the night doesn’t feel as big as Jia’s paintings.

发表评论 评论 (8 个评论)